Read the feature here.

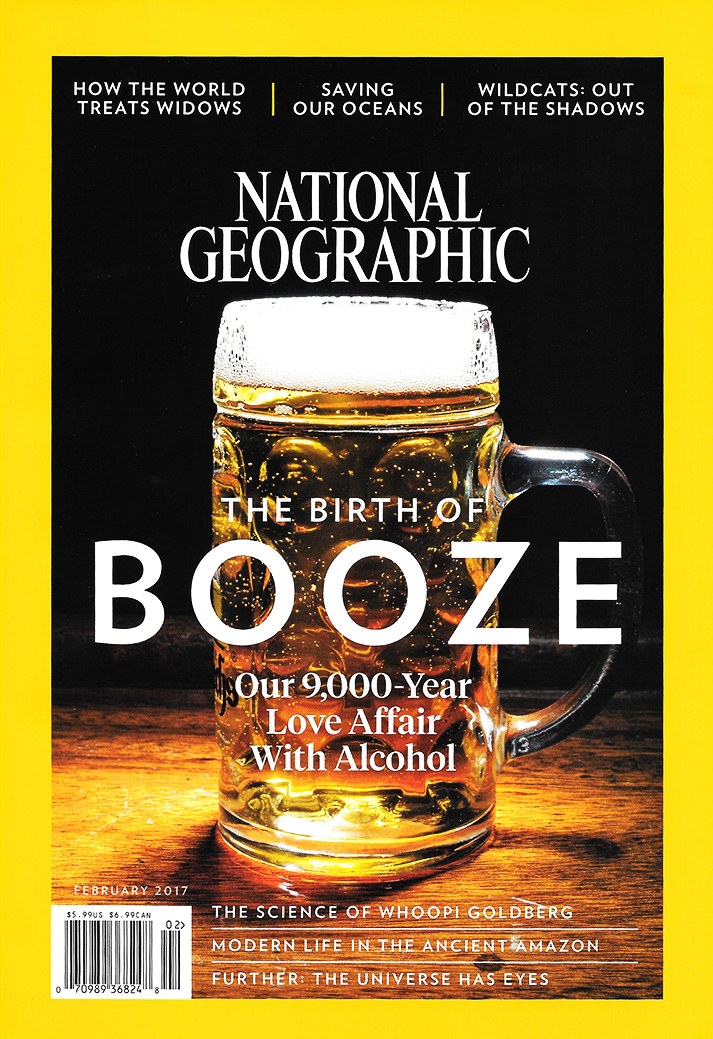

Brian Finke (b. 1976, USA) photographs life and lifestyle, using a hard flash and a hard gaze. While editorial in nature, his work’s sociological stance and lush colours make them fascinating as art, with the result that he’s published three monographs of his photographic studies, including a book on cheerleaders and football players (2-4-6-8, Umbrage Editions, 2003), Flight Attendants (powerHouse Books, 2008), and Construction (Decode Books, 2012). Over the last three years, he’s worked with National Geographic’s photo editor Todd James to take on three assignments on the complex issue of today’s food industry: the beef industry, the study of taste, and food waste. Finke tells us more about his food photos.

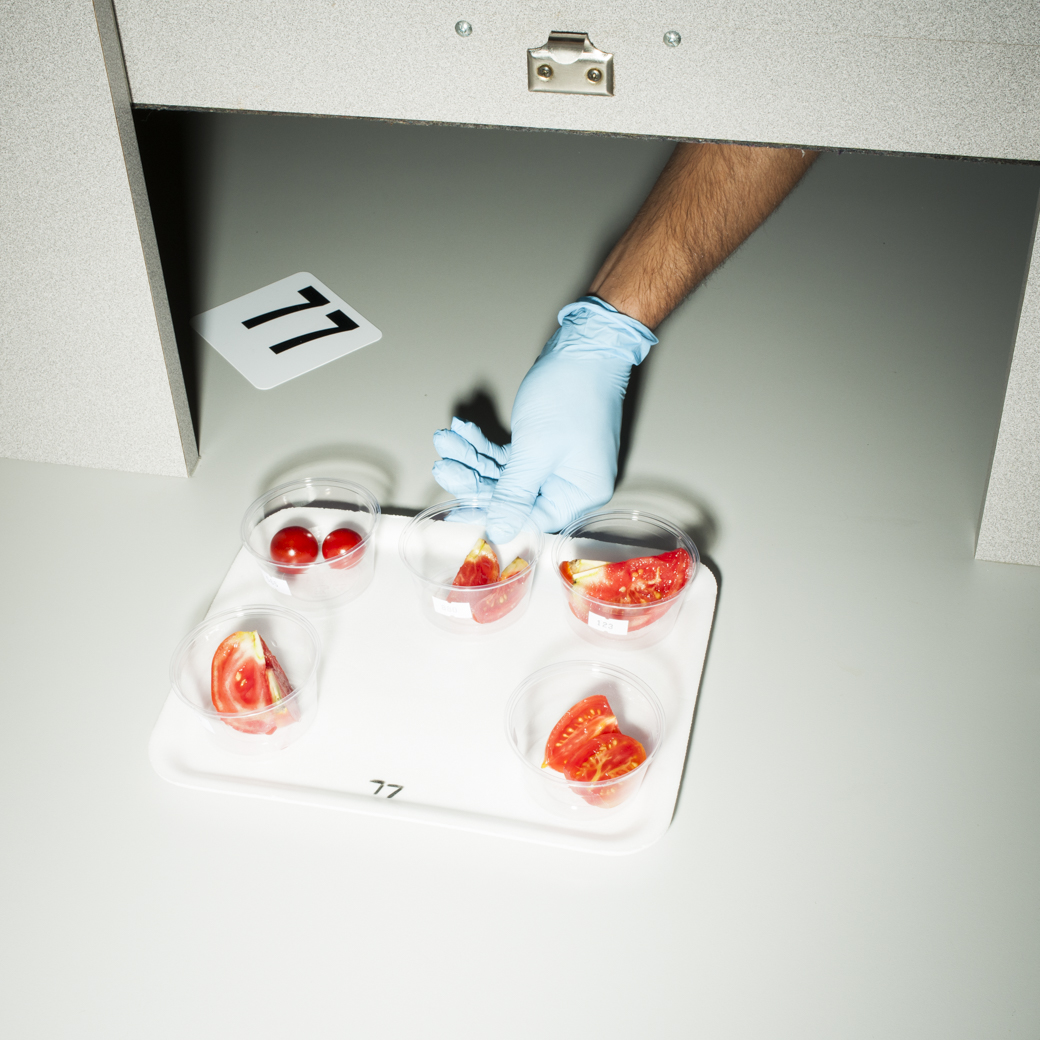

Your photo story The Science of Delicious looks at all the contemporary ways that research and expertise goes in to our sense of taste. How did that story get started?

My photo editor, Todd James, researches the topic and pretty much decides where I go. Sometimes it’s a little bit of a conversation, but he basically researches and produces it. A writer works independently from our photographs, and some of it overlaps, but his goal is basically to figure out what would be the most visually interesting narrative.

Food is great to shoot – everyone is interested in it, so there’ll always be stories about food produced. I enjoy shooting it in my style, the same way that I would photograph people or places – kind of matter-of-fact and also just the casual relatability of seeing something, shooting it and moving on.

Considering the fact that we all eat, you’d think of food as a pretty straightforward thing that we as individuals would understand easily, but your story basically tells us otherwise. Tell us about some of the research that you saw.

I loved photographing the supertasters – that’s the picture of the blue tongue. This is where they stain the tongue blue, and then they take a picture of it with a microscope – it’s basically just counting the amount of taste buds and papillae, and the more you have, the more sensitive you are to taste. My assistant and I also did the whole supertaster test. He’s a supertaster, I’m not – most of the population is not. This means, in contrast to myself, my assistant is overly sensitive to hot sauce and very strong flavours. Most chefs are not supertasters, because if they were, then food for most of the population would be very toned down – which is kind of interesting to learn.

Were the other things you were allowed to participate in?

Everywhere we go, we were eating the food and trying things out, to experience it. A neat experience was in Melbourne, photographing at the Fat Duck restaurant, which was doing a six-month popup there while they renovated their restaurant in England. It’s a tasting menu, and it’s all about senses and how sight and sound plays into taste. There’s this one dish called ‘Sound of the Sea’, which is basically like a sushi dish, but they serve the meal with an iPod and headphones, and you listen to the sound of waves crashing, and under the sushi is some foamy, frothy stuff that’s very salty so it’s like tasting the ocean, and that’s all served on top of a glass plate with sand underneath... so it’s this sight-sound-taste experience. It’s fun. It’s a very different way of eating than what I know from growing up, with eating being much more of a functional thing than an experience.

How do you try to translate that experience visually in the photographs?

Not very intentionally. (laughs) Sorry. I just go in and try to make interesting photos. I like to be very close to the situation, so the viewer is front and centre, so hopefully the experience or the situation comes across very clearly. I like that proximity, I like it to be intimate, whether it’s photographing a flavour cloud, or a catfish down in Louisiana – oh, I should tell you about the catfish, they’re interesting. They’re the supertasters of the animal kingdom. With them swimming in murky waters, they need some other way to see, so they use the sense of taste instead – it’s like their whole outside is full of taste buds and they use that to navigate the water. It’s kind of like if your tongue was taken out and stretched all around your body. When photographing it, I just like to be extremely close to the catfish in the research lab.

Was there anything that changed about your own tastes or how you experience food through this process?

I think just being aware of now seeing all the different or more elaborate ways of eating, like being in Copenhagen was pretty amazing, shooting at the Noma restaurant and in Nordic Food Lab. The whole multi-sensory experience was great – like, they bring out food and twigs are burning and you’re smelling all this different stuff.

But by the end of the trip, I just wanted to go for something quick and simple and straightforward. I love cooking myself, I love barbequing. Food is important to me, I think it’s a nice thing to share and bond over – I have two boys, and I love grilling and cooking together.

Let’s talk about your other series, Meat, in which you look at the beef industry. Beef has become a controversial food source over the last few years, not just for diet or moral reasons but also because of its environmental impact. How did that get started?

It was my first time to work for National Geographic. That same editor reached out to ask about the assignment to look at the beef industry in Texas, and I was like, “Oh my god, I’m from Texas, I would love to go back and do this and hang out with cowboys”. It originally came about from my Instagram feed actually – from posting pictures of my own barbequing and grill pictures.

That was a much more organic process, I just started out in Amarillo at some old classic ranches and just going out to meet and photograph people, then going to local butchers, and then BBQ restaurants. It’s a kind of nice and unique way that the magazine works, with the amount of time that it commits or allows for stories to grow. I was photographing probably on and off over three months, all around the state.

You visited cattle ranches, butchers, restaurants, and homes – basically the end-to-end of the cow-to-table process. How was the butcher?

I thought it was amazing. I love to eat meat, and it just seemed like a natural thing to do, to see that whole experience. The first one that we photographed was a small town artisanal butcher outside of Amarillo. It was just two dudes with knives that were five inches long – well, they would use a saw to cut the cow in half. They would kill it, drain the blood, cut it in half, then like hang it up and skin it, and then it would be in a freezer – all in twenty minutes. It was amazing watching them, and being in the room – it’s called the ‘kill floor’, and it’s painted red.

There’s a health inspector there, inspecting every cow as it’s slaughtered – and even he was like, “Is this turning you off meat?” and I’m like, “This is fucking amazing!” It just made sense to me.

There were other experiences where it was much more of the mass production type of thing, and that was a very different experience, and was much more intense. You can almost feel the death in the air, with that kind of volume, or maybe just the mental thing, just going in there and seeing everything going by...

But it was fine to see – I mean, I eat a lot of meat. It is what it is.

You’re a Texas native, where beef is basically built into the daily life. Did the photo story exploring the controversy change how you personally viewed eating beef?

I just appreciate it on the smaller scale, like with these small butchers. Seeing the giant feedlots with the thousands of cattle, it’s more about the volume. There’s environmental impacts, but... people have to eat.

Working on the food waste story, I started composting and doing other things – doing my own part, in a little way. That story influenced me more. It would just seem hypocritical to spend three months working on a story on food waste and then not change anything.

Tell us more about that story.

I shot the food waste story in September 2015, and it was photographing different activists or programs around the world that were taking positive steps to help reduce food waste. For example, in San Francisco, I photographed the Imperfect project, which is an organization that collects all the ‘ugly’ produce, to sell it at a reduced price. In a similar direction, a company up in Boston is providing food at very low cost, so people can have access to healthy food instead of buying fast food.

You said that story had the biggest impact on you. What did you see that affected you the most?

Photographing in the south of San Francisco – the produce I mentioned – and seeing the amount of food that is just dumped and goes into landfill. There was an image I shot for that of a dump truck carrying all this perfectly good lettuce. I was photographing at a transfer station, as it was going to the dump.

Perfectly good produce is dumped for various reasons. I think in this case, it was a problem of where the lettuce was being packaged, like some bags weren’t being cut properly, so everything was just being dumped. What was important in the photo is that everything looked edible – nice and fresh – and it was just amongst all the other trash as it was going to be dumped. It was interesting being there and seeing that process taking place. It drove it home very clearly.

It seems our relationship with food has become very complicated. How do you see food these days?

I think it’s nice to buy locally, but... look, I have two boys who are 8 and 11, and they’re picky eaters and it’s a pain in the ass. So, I just try to be aware of these other things. You want to enjoy food, you want to be responsible as to what you eat, and also just eat healthy, but I’ve also just got to get food in their stomachs. And try to make it interesting, too.

You mentioned Instagram earlier – are you the kind of guy to photograph your food?

Normally only when it relates to meat. It’s great to be in the backyard, grilling and drinking beer and taking meat photos.

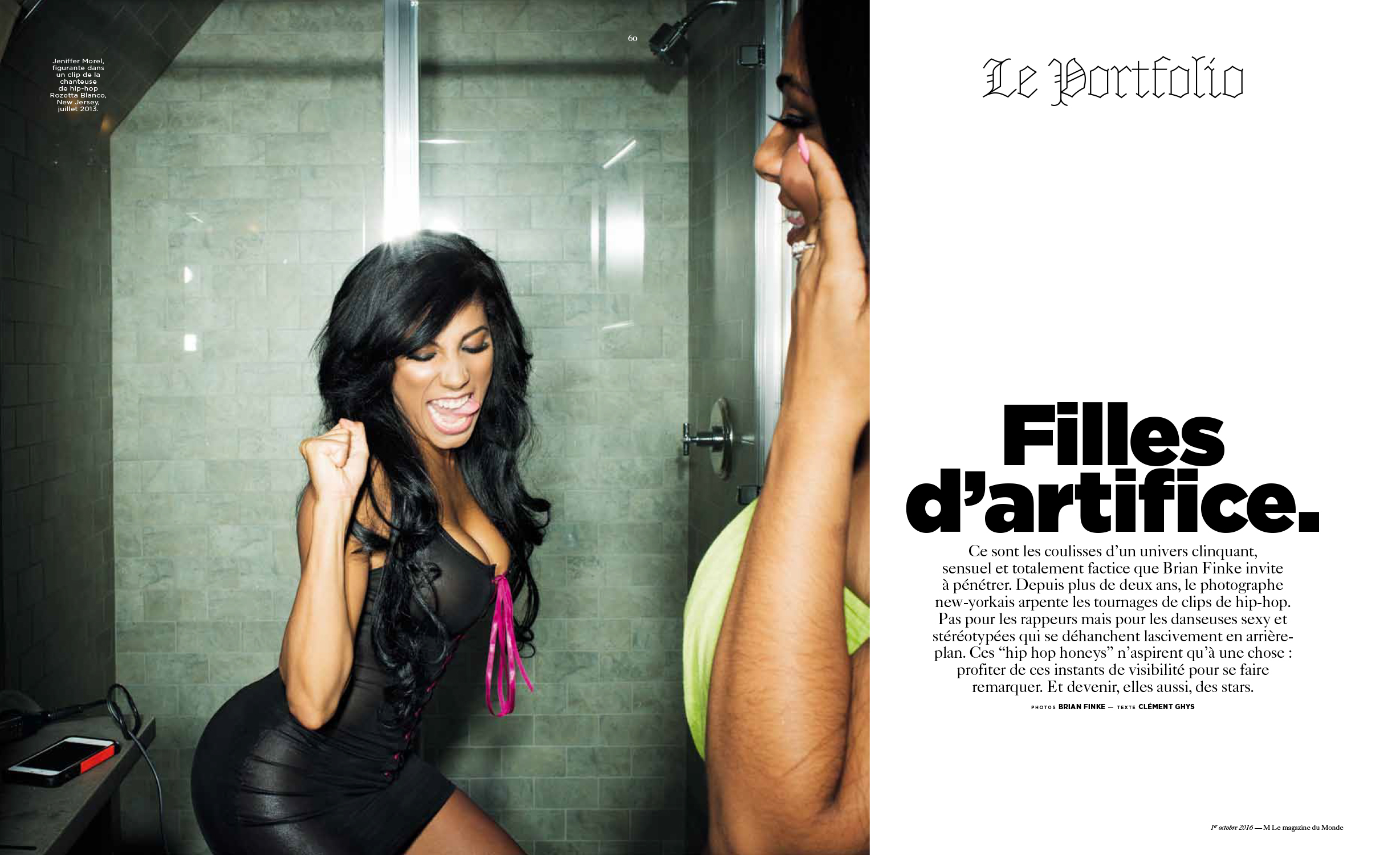

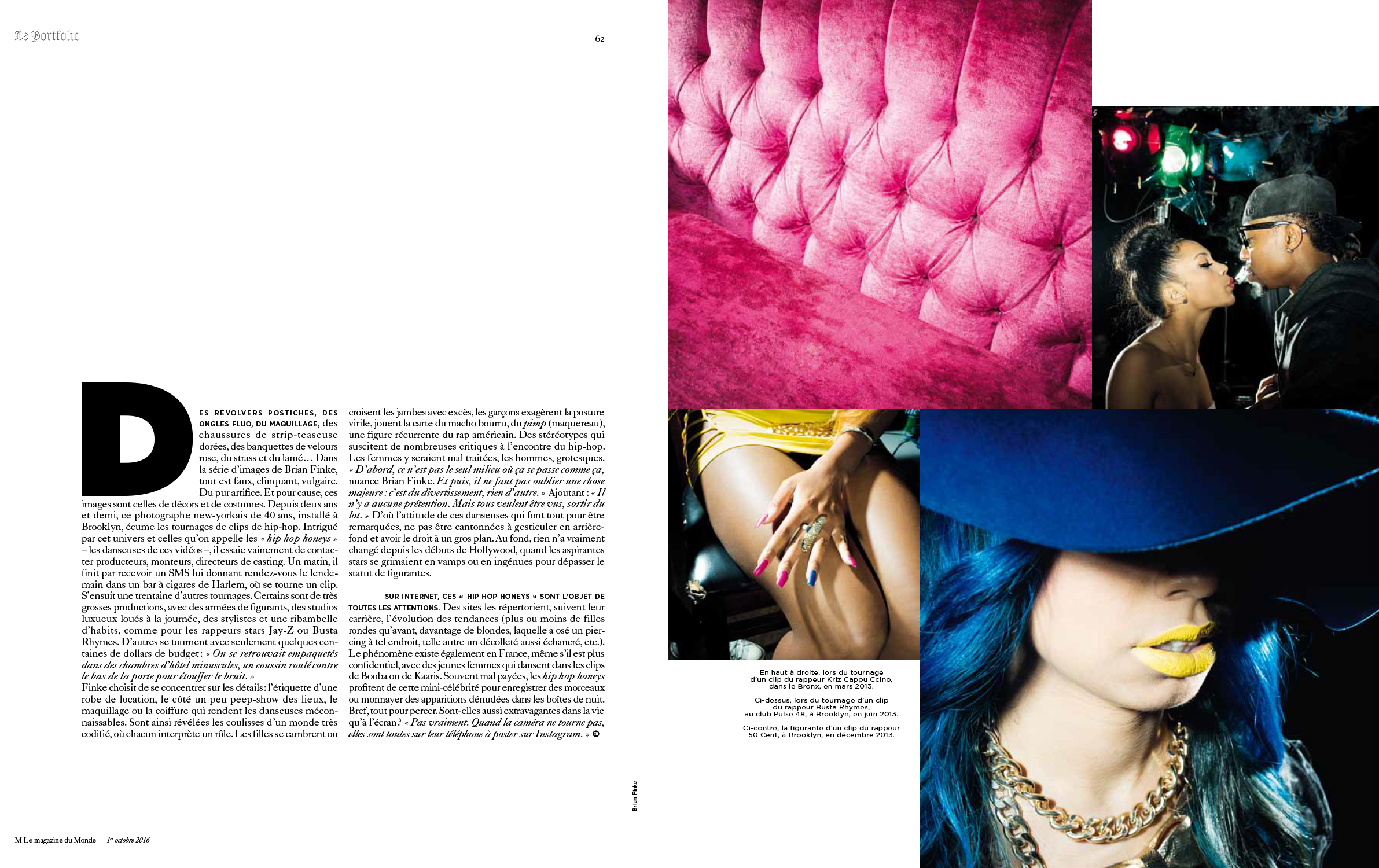

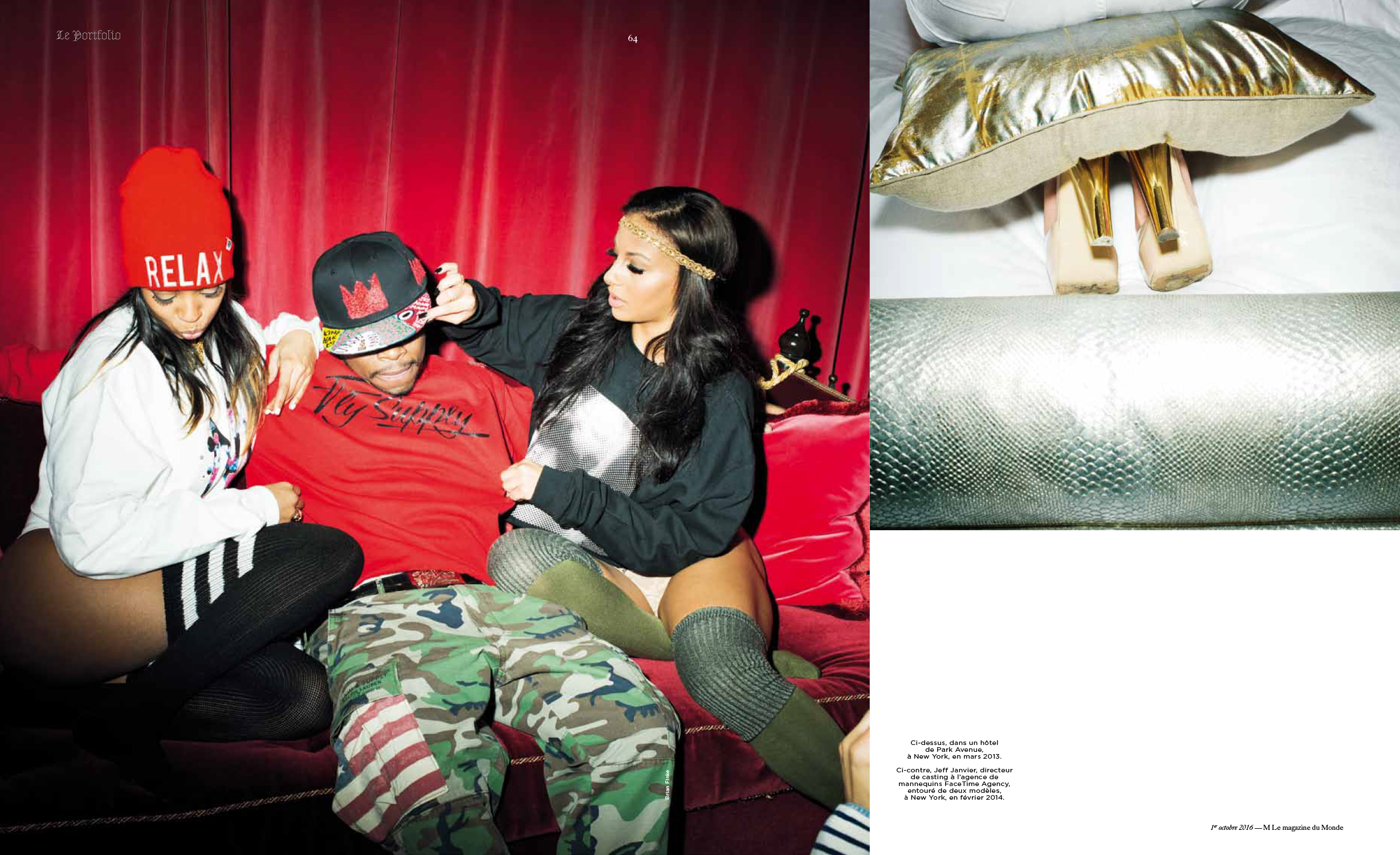

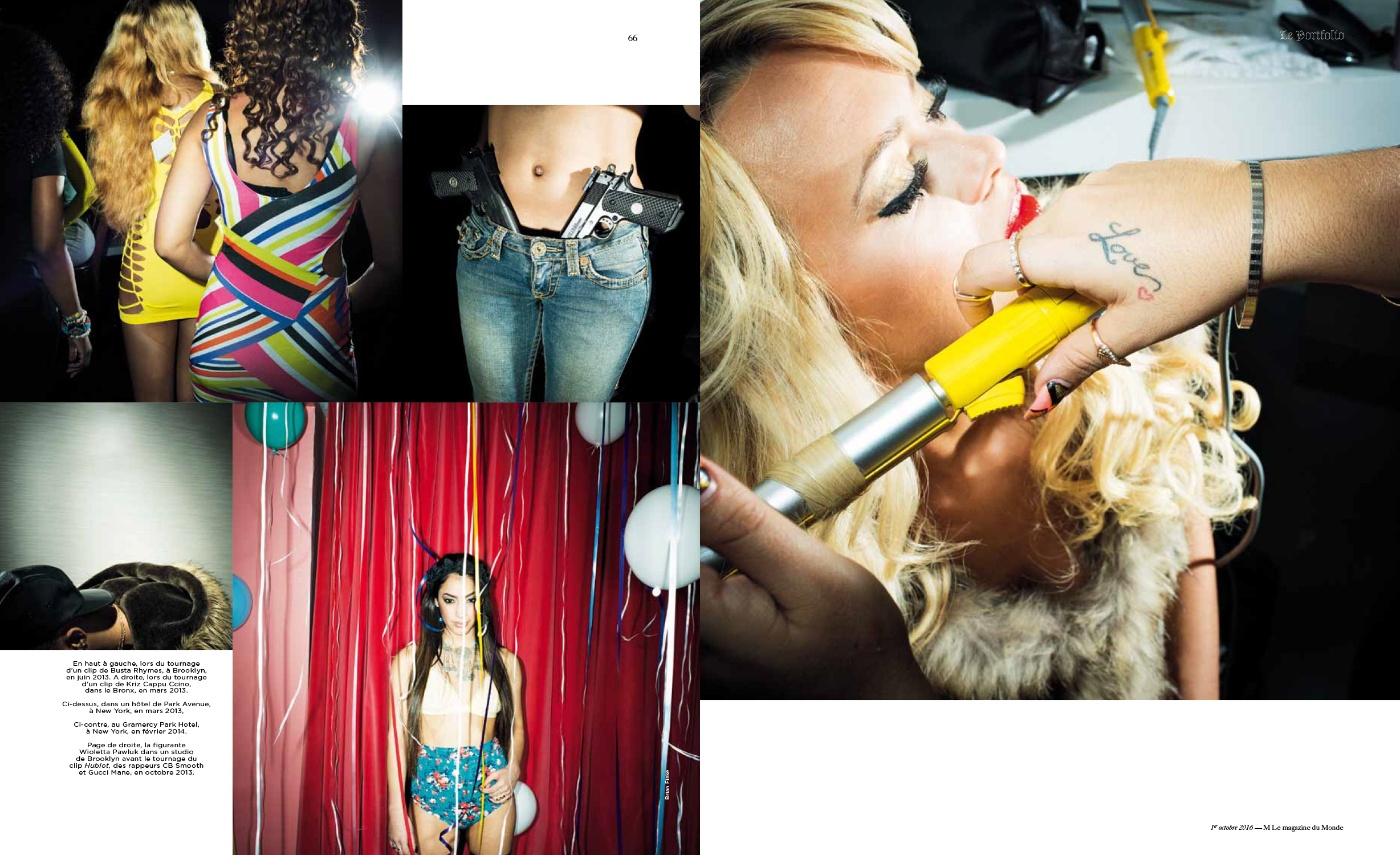

De nombreuses critiques pilonnent le hip-hop à cause de cette récurrence des clichés sexistes. Les femmes sont des objets mal traités et les hommes, des idiots engoncés dans leurs apparats grotesques. « D’abord, ce n’est pas le seul milieu où ça se passe comme ça, nuance le photographe dans M Le Monde. Et puis, il ne faut pas oublier une chose majeure : c’est du divertissement, rien d’autre ». Il ajoute enfin : « Il n’y a aucune prétention. Mais tous veulent être vus, sortir du lot ». Finalement, tout est une question de recul.

De nombreuses critiques pilonnent le hip-hop à cause de cette récurrence des clichés sexistes. Les femmes sont des objets mal traités et les hommes, des idiots engoncés dans leurs apparats grotesques. « D’abord, ce n’est pas le seul milieu où ça se passe comme ça, nuance le photographe dans M Le Monde. Et puis, il ne faut pas oublier une chose majeure : c’est du divertissement, rien d’autre ». Il ajoute enfin : « Il n’y a aucune prétention. Mais tous veulent être vus, sortir du lot ». Finalement, tout est une question de recul.