Read the feature here.

How to Make Baby Bees and Other Weird Stuff Great to Eat.

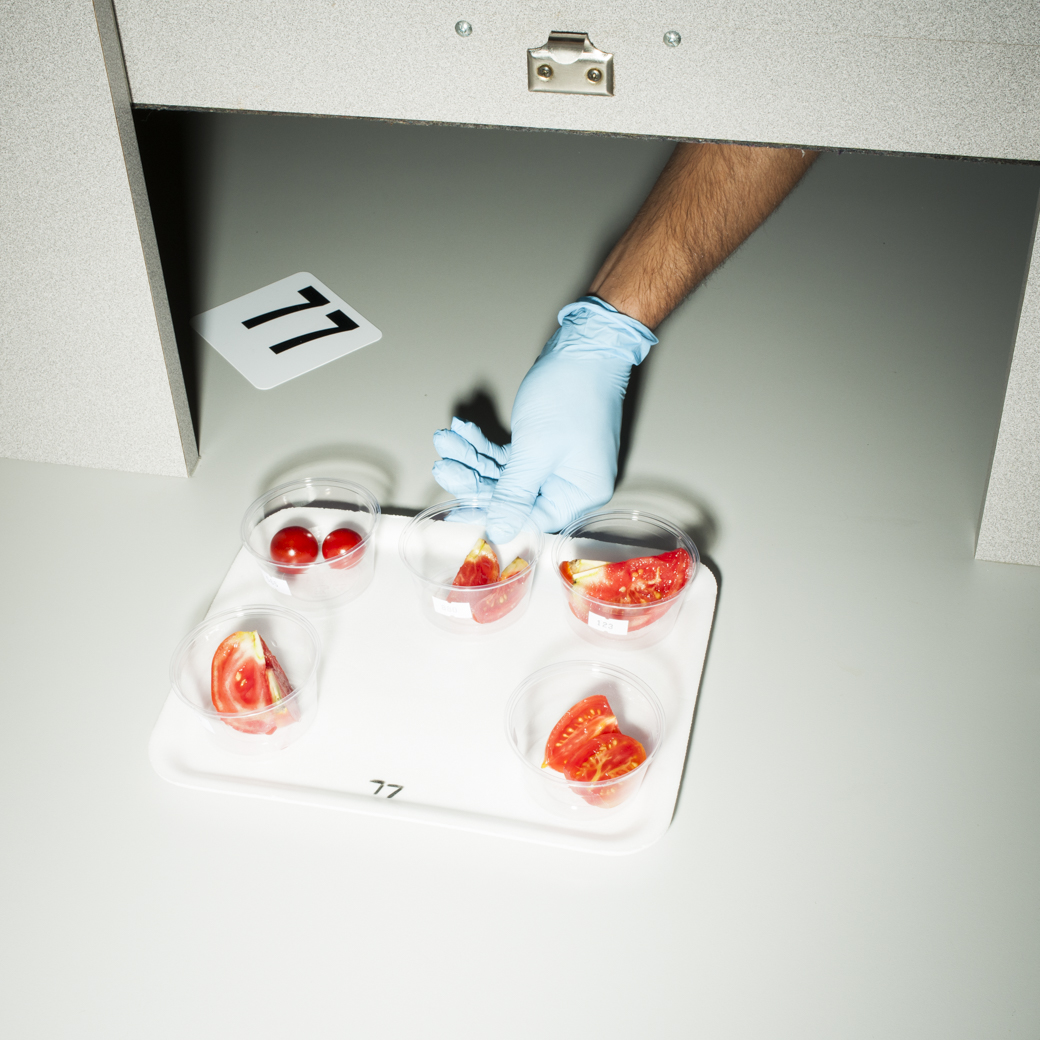

Finke isn’t a foodie. He’s a photographer. He spent last summer shooting The Science of Delicious for National Geographic. The trip took him from a lab in Florida where scientists engineer tastier tomatoes to an experimental food workshop in Toronto where people inhale flavor clouds. And that was the normal stuff.

The weird stuff included a visit to Louisiana State University, where scientists study catfish to better understand taste. The whiskered bottom-feeders navigate murky water using tens of thousands of tastebuds that cover their bodies. “It’s the same idea as if you took your tongue and, like, stretched it around your body,” Finke says.

Later, at the University of Florida, Finke discovered that he isn’t a supertaster. Such people have an unusually high number of papillae, the bumps on your tongue that contain taste receptors, and it makes them hypsersensitive to flavors. Experimental psychologist Linda Bartoshuk coined the term in the early 1990s. Her team tested Finke, who isn’t a supertaster, and his assistant, who is. “He doesn’t like foods that I would think are deliciously spicy, because it’s too much for his palate,” Finke says.

Not being a supertaster might explain why Finke is so gastronomically adventurous. When the folks at Nordic Food Lab, the Copenhagen outfit that investigates “food diversity and deliciousness,” offered him a few bee larvae, he happily popped them into his mouth. Oddly, he doesn’t remember how they taste—“Maybe crunchy? Maybe not crunchy?”—but he quite liked ants. “They have a very strong flavor,” he says. “Salty and robust.”

Finke visited 10 labs, cooking schools and restaurants like the Fat Duck in Melbourne, where the sorbet comes with a box of steaming oak moss that you sniff while eating. He shot, as he always does, with a Nikon D800 and off-camera flashes that cast everything in an unappetizing glow.

The project opened his eyes to the bizarre lengths people go in pursuit of flavor. But if you love food, you’ll try anything. Even ants.

No comments.